While reading the second part of Michael's interview, I guess many perfume lovers wished everybody in the perfume industry would see his advice given the boredom of many new launches. Finally let's hear what Michael said about the fragrance market, EU regulations on raw materials and more.

While reading the second part of Michael's interview, I guess many perfume lovers wished everybody in the perfume industry would see his advice given the boredom of many new launches. Finally let's hear what Michael said about the fragrance market, EU regulations on raw materials and more. E: Your fragrance classification helped a loto of retailers selling fragrances and nowadays more and more they rely on your guide to advice their customers also to find fragrance substituites for their beloved discontinued juices. But how the retail model has changed during these 30 years and how it will evolve in the future?

M: Very interesting question. The fragrance that started the whole business changing was Charlie in 1973 because before Charlie, perfume was a gift: men mostly bought perfume and gave it to women to be used on special occasions. But it was about that time that women started in the western world to move from home to office, they had money, a new generation. Charlie was the one in the States and then in Europe that triggered this thing: “Oh it’s so nice, I’m gonna wear it. I may start to wear it during the day”.

Then it came our first blockbuster, Opium in 1977. By the end of the '70s women were spending more money on buying perfume for themselves and men were spending on giving it too and THAT is what changed the whole equation because suddenly retailes started to set up, take notes and the broad big brands started to buy all these perfumes.

Then it came our first blockbuster, Opium in 1977. By the end of the '70s women were spending more money on buying perfume for themselves and men were spending on giving it too and THAT is what changed the whole equation because suddenly retailes started to set up, take notes and the broad big brands started to buy all these perfumes.But I have to say the fragrance that really changed the whole thing after that was Giorgio. Giorgio came up in 1981 and by chance it was picked up by Bloomingdales in 1983 for an Italian promotion and became a sensation. Blomingdales had Giorgio exclusively for four years then the Giorgio people, as a friend of mines who worked over there told me, they would once send pre-scented cards put into envelopes.

The problem is that in 1982 the American Post Office said - "If you use that we’ve got to charge you a premium. You have to find something that is bound into the magazine" - and that is what forced the scent strips revolution, that regulation coming from the American Postal Services. Well, Giorgio was not the first to use scent strips but the first to really understand their potential. Nobody had ever sampled that business before and Giorgio exploded and became one of the cultural events of New York: you went to New York to see the Empire State Building, to see the Statue of Liberty and you went into Bloomingdales to see Giorgio. Giorgio changed the retailers perception of fragrance forever. Suddenly perfume was not just necessary, but a cool product. It changed the pace of innovation because the retailers said - “Wow I want something new, what I know is what you did for me last year but what have you got for me next year” - because at the end of the day retailers would turn it into events. Products bring customers through the door, that’s why they say: “New! New! New!”

E: Recently I've seen again this call for “New! New! New!” but how did it go?

M: Now the interesting thing is how it developed things into niche and the opening of the specialized boutiques. More and more we’ve seen fragrance moving away from the old fashioned department stores and go into almost stand alone boutiques. Think of how Bath&Body Works or Victoria Secrets have developed. In many ways think of what’s happening with the Annick Goutal or By Kilian or Byredo opening their boutiques and stuff like this. Think of the Tom Ford boutiques: this is one the key new trend and is going to continue because the reality is that the cost of operating in most of top department stores has got so horrendous and they’re demanding so much that it is getting costly the development of brands like that.

E: A true gentleman, a precious source of knowledge for perfume writers and a refetence for the perfume industry. In a nutshell “The perfume expert’s expert”. All these sentences suits you perfectly and surely your work contributed to set a reference in the modern perfume history. But which have been the most influencing persons during all these years?

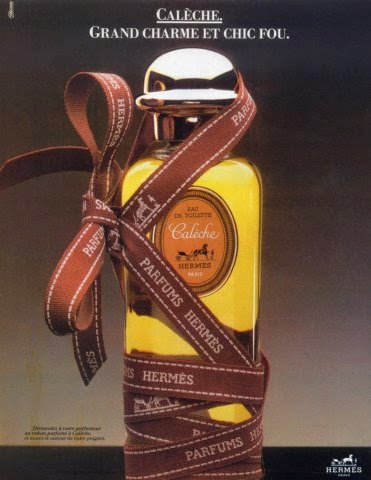

M: Probably the single most influencing person is Guy Robert. I first met Guy in 1980. He was the perfumer who developed Calèche, Madame Rochas, most o the early Guccis, one of the great masters of the XX century perfumery. He was the nephew of Henri Robert who did Chanel No. 19, he was the grandson of François Robert who trained François Coty for example at Rallet. I met him shortly after he became the president of the French Society of Perfumers. It was about that time I started talking to him about Perfume Legends. Something tickled his imagination and he was so incredible, I would spend hours and hours and hours just listening to him. He taught me so so much and still I got a fraction of what he gave to me. He opened doors to me, he was amazing. Then he translated Perfume Legends into French and for the last 16 years he became my technical consultant for the guide Fragrances of the world. He died sadly last year and I’m missing him unbelievably. Every now and then I say “Guy, what would you do on this?”

M: Probably the single most influencing person is Guy Robert. I first met Guy in 1980. He was the perfumer who developed Calèche, Madame Rochas, most o the early Guccis, one of the great masters of the XX century perfumery. He was the nephew of Henri Robert who did Chanel No. 19, he was the grandson of François Robert who trained François Coty for example at Rallet. I met him shortly after he became the president of the French Society of Perfumers. It was about that time I started talking to him about Perfume Legends. Something tickled his imagination and he was so incredible, I would spend hours and hours and hours just listening to him. He taught me so so much and still I got a fraction of what he gave to me. He opened doors to me, he was amazing. Then he translated Perfume Legends into French and for the last 16 years he became my technical consultant for the guide Fragrances of the world. He died sadly last year and I’m missing him unbelievably. Every now and then I say “Guy, what would you do on this?”Melancholy veils a bit Michel's voice moving me to a deep respect for their friendship.

M: The other great one of course was Edmond Roudnitska. Not that I knew him very well, it was a very formal relationship, but I wrote to him hoping that he would receive me to talk about his work for Perfume Legends. You know that he became famous in 1944 with the creation of Femme and with the money that brought him (because perfumers were payed on commission at that stage) he started out his own company at Cabris. He did very few fragrances in his life but when you think of Diorissimo, Diorella and Eau Sauvage, I mean, these are milestones that changed perfumery. I don’t want to talk to you about his work but he was also the only living perfumer who had known some of the great perfumers such as Ernest Beaux and Alméras from Patou because he started working in 1927. When I wrote him I thought I’ve been lucky if he agreed to receive me and if he did give me time, maybe 15 minutes. What he did say was: “Come and see me” and to my surprise something ticked his imagination and he gave me over three hours in fact.

It was he and Guy Robert that opened the doors to me and in the end I interviewe just shorter than a 160 people: couturiers, bottle designers, perfumers, heads of companes and I suspect none of them might never agree to see me if it’d not be for Guy and Monsieur Roudnitska. Sadly Monsieur Roudnitska never saw the book: he wrote the foreword to it but he died three weeks before it was published so I dedicated it to him. So those two would be the ones.

E: Any other remarkable personality in the perfume industry you regret you didn't meet?

M: If there’s another person I’d have loved to meet it would be François Coty. The man was a genius and gave us three of the perfume families: orientals, chypres and floral orientals with L’Origan. He gave us the same techniques of merchandizing we use these days putting one fragrance in a window, highlighting leave it on. Before Lauder came out to give a purchase, he was using that. He was the first to commission bottle designers to create special bottles because he said that a perfume would have been a treasure . First to use market research: every year he would come out at Christmas with a new fragrance called Le Parfum Inconnu, the unknown fragrance. If it worked, it would have been launched the next year with its proper name. That’s a great market research! Haha!

As you know he died with not much money, but with his dead he seeded the entire French industry: think of Armand Petitjean of Lancôme that has been his general manager and before that his agent for Brazil. Lancôme came out with no less than five perfumes to start with. So Heftler Louiche at Christian Dior that had been general manager then before that financial director for François Coty. George Baugue who created Piguet and has been financial director and many others. The man was a genius! And yet there isn’t even a room dedicated to him into the International Perfume Museum in Grasse, is that sad, isn’t it?

E: Oh yes, I’ve been there the last year to visit the Poiret exhibition and there was given no special remark for Coty’s work, but now let's go to the next question.

As a perfume expert, you helped a lot with your work in breaking down false myths about perfumery. Nowadays people are more conscious, they get information from books and the web but there’s still much to do.For example nowadays many people are concerned about 100% natural perfumery. But talk to me about your experience with this mystical confusion behind raw materials.

M: Oh, I love these naturals, I think they’re beautiful, they’re marvelous but I don’t think they’re creative. It was Jicky in 1889 that turned perfume into an art because for the first time we started to see the new experience some of the new molecules could add to the marvelous fine naturals. For me a great perfume has probably got a body of fine naturals bound to a skeleton of innovative synthetic aromanotes. Let’s face that most of the aromanotes come from nature in fact. If you take jasmine you get over 800 different natural chemicals put together. So when people talk to me in harsh terms about synthetics I always say I want something different. Perfume must be a new experience to me. But I mean, I know a lot of people that would disagree with me and I can quite understand that. Anyway it’s important to make people understand the truth about raw materials.

M: Oh, I love these naturals, I think they’re beautiful, they’re marvelous but I don’t think they’re creative. It was Jicky in 1889 that turned perfume into an art because for the first time we started to see the new experience some of the new molecules could add to the marvelous fine naturals. For me a great perfume has probably got a body of fine naturals bound to a skeleton of innovative synthetic aromanotes. Let’s face that most of the aromanotes come from nature in fact. If you take jasmine you get over 800 different natural chemicals put together. So when people talk to me in harsh terms about synthetics I always say I want something different. Perfume must be a new experience to me. But I mean, I know a lot of people that would disagree with me and I can quite understand that. Anyway it’s important to make people understand the truth about raw materials.E: During the last months the proposal for new EU regulations on raw materials to be approved before summer started a discussion among perfume lovers on the web whether perfumery should be protected as a cultural heritage and a form of art or craftmanship like wine or food rather than being simply ruled to protect health. Is it possible to find a way to take care of all these aspects of perfumery?

M: I'm devastated by what is happening with IFRA. If I could do anything for changing things, I would do it. I asked Mark Behnke. Mark is a very renouned scientist and we were talking about this one day. He said: "You know, there's very little reputable scientific evidence to support what they say". "You're going to be kidding" I said. He said no and he send me a lot of papers. The reality is that the only evidence are two studies I came across that could be considered scientific in the sense they're based on double blind studies and things like that. Almost all the other evidence is based on principles that any scientist would burnout. The reality is this is what we have to do with and that's the bad side.

The good side is Luca Turin has a lovely quotation. He sais: "A perfumer is influently creative, he's going to find a way to get around this" and he's right. So it's not the end fine perfumery but is going to be a different perfumery. Another good thought for you: I was recently talking to a young perfumer from Brazil who did some of the big Natura and O' Boticario fragrances and he said: "I regret some great naturals we cannot longer use obviously, but I'm so excited by the potential of some of the new molecules". So it's a whole different way of looking at life.

It's been a real pleasure to talk to you dear Michael. Actually I could listen to you for hours and hours and I feel really spoiled for having had such a great honour to interview you. Thank you very much!

<part 1> <part 2>

Nessun commento:

Posta un commento